In a seemingly-forgotten corner of the state, sits the seemingly-forgotten town of Elaine. The town was established back in 1911 and was surrounded by large cotton plantations. In modern times, Elaine has suffered the same fate as many other Delta towns. Farm mechanization eliminated the need for most agricultural workers, and The Great Migration saw thousands of African Americans leave the Delta for better jobs and opportunities in the North. Elaine, with its dark history, was left behind.

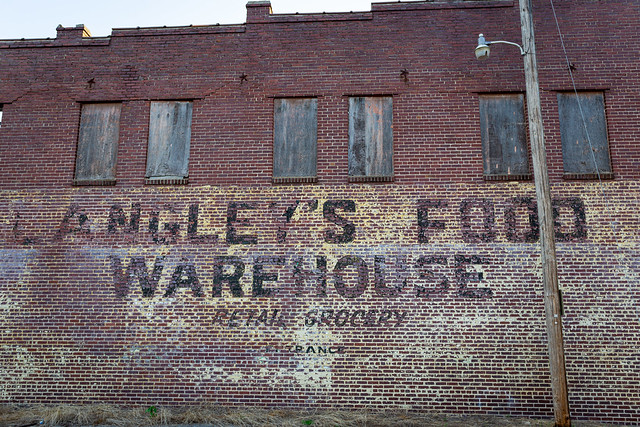

Most of the buidlings along Main Street in Elaine are empty, including the old Lee Grocery Store. Constructed in 1915, it served as a grocery store until 2010. There are plans to turn the old building into a visitor's center.

Across the street is the shell of another old building, with just a few walls still standing.

Along an interior corner of the old building was this tree, defiantly growing up out of the concrete floor.

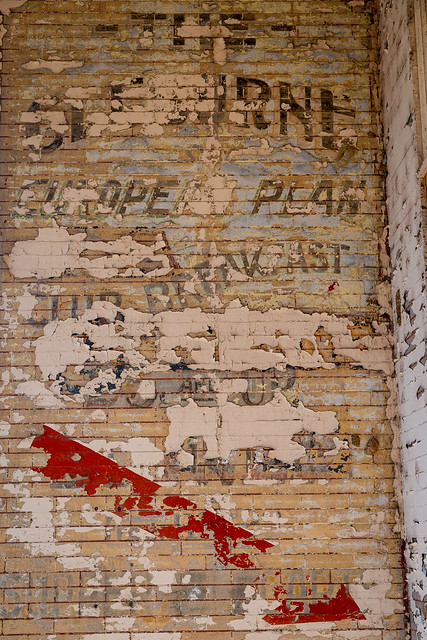

If you look closely, there are a few birdhouses on the tree. Those are part of an effort to turn Elaine into the "Birdhouse Captiol of the US." There are hundreds of birdhouses scattered throughout the town (in fact there are more birdhouses than people here). They are on trees, along the side of buildings, and they occupy the storefronts of buildings along Main Street. That includes this window, with this ominous-sounding sign.

There is one major piece of history in Elaine, one that has also been mostly forgotten (or ignored) for decades. In 1919, this small town was the epicenter of one of the worst mass lynchings in US history. The exact number of people killed is unknown, but estimates are that several hundred people were murdered in and around Elaine. From the

Encyclopedia of Arkansas History:

The conflict began on the night of September 30, 1919, when approximately 100 African Americans, mostly sharecroppers on the plantations of white landowners, attended a meeting of the Progressive Farmers and Household Union of America at a church in Hoop Spur (Phillips County), three miles north of Elaine. The purpose of the meeting, one of several by black sharecroppers in the Elaine area during the previous months, was to obtain better payments for their cotton crops from the white plantation owners who dominated the area during the Jim Crow era. Black sharecroppers were often exploited in their efforts to collect payment for their cotton crops."

Leaders of the Hoop Spur union had placed armed guards around the church to prevent disruption of their meeting and intelligence gathering by white opponents. Though accounts of who fired the first shots are in sharp conflict, a shootout in front of the church on the night of September 30, 1919, between the armed black guards around the church and three individuals whose vehicle was parked in front of the church resulted in the death of W. A. Adkins, a white security officer for the Missouri-Pacific Railroad, and the wounding of Charles Pratt, Phillips County’s white deputy sheriff.

This is the stretch of road where the Hoop Spur church once stood. The church no longer exists, it was burned down shortly after the shooting.

The massacre was one of many that occurred that year during the aptly named "Red Summer," which saw violence occur in cities across the country. Visiting the fields around Hoop Spur and Elaine now, it seems like the landscape has not changed all that much (except that the fields grow soybeans now instead of cotton).

The fields and forests around Elaine and Hoop Spur would become the scenes of gruesome violence. More from the Encyclopedia of Arkansas History:

The next morning, the Phillips County sheriff sent out a posse to arrest those suspected of being involved in the shooting. Although the posse encountered minimal resistance from the black residents of the area around Elaine, the fear of African Americans, who outnumbered whites in this area of Phillips County by a ratio of ten to one, led an estimated 500 to 1,000 armed white people—mostly from the surrounding Arkansas counties but also from across the river in Mississippi—to travel to Elaine to put down what was characterized by them as an “insurrection.” On October 1, Phillips County authorities sent three telegrams to Gov. Brough, requesting that U.S. troops be sent to Elaine. Brough responded by gaining permission from the Department of War to send more than 500 battle-tested troops from Camp Pike, outside of Little Rock (Pulaski County).

After troops arrived in Elaine on the morning of October 2, 1919, the white mobs began to depart the area and return to their homes. The military placed several hundred African Americans in makeshift stockades until they could be questioned and vouched for by their white employers. (Union leader Robert Lee Hill was hidden by friends during the violence and later escaped to Kansas.) The violence even claimed those who had nothing to do with the union efforts, such as brothers David Augustine Elihue Johnston, Gibson Allen Johnston, Lewis Harrison (L. H.) Johnston, and Leroy Johnston, who were returning to Helena from a hunting trip when they were attacked and killed on October 2.

Evidence shows that the mobs of whites slaughtered African Americans in and around Elaine. For example, H. F. Smiddy, one of the white witnesses to the massacre, swore in an eye-witness account in 1921 that “several hundred of them… began to hunt negroes and shotting [sic] them as they came to them.” Anecdotal evidence also suggests that the troops from Camp Pike engaged in indiscriminate killing of African Americans in the area, which, if true, was a replication of past militia activity to put down perceived black revolts. In 1925, Sharpe Dunaway, an employee of the Arkansas Gazette, alleged that soldiers in Elaine had “committed one murder after another with all the calm deliberation in the world, either too heartless to realize the enormity of their crimes, or too drunk on moonshine to give a continental darn.”

The extent of the violence isn't well known. Many African-Americans attempted to hide in the nearby swamps, while others were shot in the cotton fields while they worked. I don't know if it was my imagination, but there was definitely an uncomfortable and eerie feeling in the fields. An overwhelming sense that something bad had happened here seems to have seeped into the soil, and was as thick in the air as the summer humidity.

It does seem like history haunts these fields. It was eerily silent there, except for the buzzing of a crop-duster flying low above the crops.

Continuing from the Encyclopedia of Arkansas History, who explain it better than I can:

From this point forward, two versions of what occurred at Elaine exist. The white leaders put forward their view that black residents had been about to revolt. E. M. Allen, a planter and real estate developer who became the spokesman for Phillips County’s white power structure, told the Helena World on October 7, “The present trouble with the Negroes in Phillips County is not a race riot. It is a deliberately planned insurrection of the Negroes against the whites directed by an organization known as the ‘Progressive Farmers and Household Union of America,’ established for the purpose of banding Negroes together for the killing of white people.”

On the other hand, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in New York, which had sent Field Secretary Walter White to investigate the events in Elaine, contested such allegations from the outset. White wrote in the Chicago Daily News on October 19, 1919, that the belief there had been an insurrection was “only a figment of the imagination of Arkansas whites and not based on fact.” He said, “White men in Helena told me that more than one hundred Negroes were killed.” Famed journalist and anti-lynching activist Ida B. Wells-Barnett secretly interviewed some of the prisoners in Helena, from which she produced the pamphlet “The Arkansas Race Riot.” This work also challenged allegations of an insurrection and documented the torture and other depredations the prisoners had suffered.

Within days of the initial shoot-out, 285 African Americans were taken from the temporary stockades to the jail in Helena, the county seat, although the jail had space for only forty-eight. Two white members of the Phillips County posse, T. K. Jones and H. F. Smiddy, stated in sworn affidavits in 1921 that they committed acts of torture at the Phillips County jail and named others who had also participated in the torture. On October 31, 1919, the Phillips County grand jury charged 122 African Americans with crimes stemming from the racial disturbances. The charges ranged from murder to nightriding, a charge akin to terroristic threatening (as defined by Act 112 of 1909). The trials began the next week, with John Elvis Miller leading the prosecution. White attorneys from Helena were appointed by Circuit Judge J. M. Jackson to represent the first twelve black men to go to trial. Attorney Jacob Fink, who was appointed to represent Frank Hicks, admitted to the jury that he had not interviewed any witnesses. He made no motion for a change of venue, nor did he challenge a single prospective juror, taking the first twelve called. By November 5, 1919, the first twelve black men given trials had been convicted of murder and sentenced to die in the electric chair. As a result, sixty-five others quickly entered plea-bargains and accepted sentences of up to twenty-one years for second-degree murder. Others had their charges dismissed or ultimately were not prosecuted.

The massacre and the sharecroppers sentenced to death drew the attention of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). Through grassroots efforts, the NAACP built support for the sharecroppers dubbed the “Elaine Twelve” and raised money for their legal counsel. It was in the defense of the Elaine Twelve that Scipio Jones, one of the lawyers for the twelve, rose to national acclaim. Scipio Jones and the NAACP’s defense team worked to free the twelve defendants, who were divided into the Moore v. Dempsey and Ware v. Dempsey cases. On February 19, 1923, the U.S. Supreme Court handed down a 6–2 decision in favor of the Moore defendants, maintaining the Twelve had been denied “due process” and noting the judicial proceedings had been influenced by a mob that had assembled outside of the courthouse before the men were sentenced. Despite the favorable ruling from the U.S. Supreme Court, the Moore defendants remained in jail facing a re-trial in district court. On November 3, 1923, Governor McRae commuted the death sentences of the sharecroppers to twelve-year terms in prison, making them immediately eligible for parole. On January 13, 1925, the six Moore defendants were granted indefinite furloughs from McRae and were released from jail.

The events at Elaine were then largely forgotten in the decades since (except, of course, by the people who lived through it and their descendants). I grew up in Arkansas and never learned about it in any history class. The haunted landscape surrounding these fields in Phillips County still remains.

For the massacre's 100th anniversary last year, a memorial was constructed by the courthouse in Helena-West Helena. But in Elaine, a tree that had been planted to memorialize the victims was cut down in the middle of the night.

How do you even begin to memorialize something as traumatic and awful as this? How do you reconcile a century of animosity and anger, which sadly is still evident today? This is a state that is in many ways still fighting the Civil War, so it's no surprise that a massacre in 1919 is an unhealed wound.

This was written in the late summer of 2020, a year that has been marked by months of protests for the idea of racial justice and equality. I look at my kids, and I wonder how we are going to fix all of this for the future generations. The difficulties we are experiencing will not be solved unless we deal with the unfortunate history of our past. We need to recognize the tragedies that have occurred before us, and strive to make sure that we are growing past them together.